Disaster on the Red

By Russell Cappo Jr. NAI

|

|

Shreveporters now have a bit of their local history on display. In 1995, shortly after the Joe D. Waggoner Lock & Dam #5 was completed, the wreck of the steamboat “Kentucky” was discovered. The story of this ill-fated boat is tied to Shreveport and the end of the Civil War.

The “Kentucky” was constructed as a side-wheeler steamboat at Cincinnati, Ohio in 1856. The vessel was recorded officially as having a length of 222 ft., a beam of 32 ft., depth of 5 ft. 6 in. and a capacity of 375 tons. The Kentucky was built as a large, elegant packet for use on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers and was similar in layout to hundreds of other steamboats that worked on those waters.

|

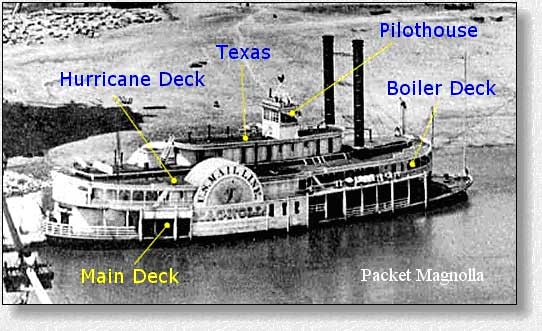

The main deck served as the principal cargo deck. Above the main deck was the boiler deck, where the passenger accommodations were located. A long, narrow cabin was centrally located, with staterooms opening onto it from the sides. The Kentucky had 52 staterooms furnished with bedding: her cabins boasted carpet, chairs, a sofa, tables and tableware. The sexes typically were segregated aboard packet boats, with the gentlemen's salon located forward and the ladies' cabin aft. Above the boiler deck was the hurricane deck and the crew quarters, and officers were quartered in the Texas deck on the next level. The pilothouse was atop the Texas, aft of the chimneys.

The following picture is a typical packet steamboat deck layout showing the various decks aboard the side-wheeler Magnolla. The Magnolla was much smaller than the Kentucky.

The Kentucky's first owners were the Cincinnati, Maysville, and Portsmouth U.S. Mail Line Company (the US Mail Line also owned the much smaller Magnolla of the above picture). Captain B. Kepner was her first master. A U.S Mail Line service implied regularly scheduled and punctual trips with penalties for non-performance. In 1858, ownership of the vessel was transferred to the Cincinnati and Louisville U.S. Mail Line Co., the oldest and best known of the western steamboat lines. During the following year, the Kentucky's home port was transferred from Cincinnati to Louisville, Kentucky. The vessel was sold in 1860 to I. M Gosler of the Memphis and New Orleans Steam Packet Co. and was re-enrolled on April 10 at the Port of Memphis with James Lee as her Master. Three months later the vessel was enrolled yet again, this time by the Memphis & New Orleans Steam Packet Company. The Memphis & New Orleans Line ran in conjunction with the Memphis and Charleston Railroad for several seasons preceding the Civil War. The company, however, lost money and the boats were sold, with substantial losses to the stockholders. Six months later, in October, 1860, the vessel was enrolled under new ownership, although James Lee continued as her captain.

The Civil War

The Kentucky was in her homeport of Memphis at the outbreak of the Civil War. Shortly thereafter, the vessel was purchased by Preston Lodwick. With tensions increasing, Lodwick, wanting to return north, boarded the Kentucky and tried to slip past the authorities in Memphis. Lodwich miscalculated the vigilance of the Confederates at Memphis who turned him back. Finally abandoning the boat just above Island No.10, he escaped on foot to Illinois. Confederate authorities ordered the boat to be burned, but the chief engineer, James Keniston, assumed the duties of captain and ran it “under duress” as directed by the Confederates.

Keniston continued to operate the vessel as a Confederate transport until June, 1862. Little is known of the operation of the Kentucky while she remained in Confederate hands. Keniston later professed his allegiance to the Union and claimed he acted under duress. He even swore that at one point he almost succeeded in getting the boat into Union hands on the White River, but the Confederate authorities changed his course to Little Rock , ironically, the captain of the Kentucky was cited in November 1861 by the Confederate army for exhibiting "fearlessness and energy deserving the highest praise" under fire for ten days and nights spent ferrying Major General Leonidas Polk's troops across the Mississippi between Columbus, Kentucky, and Belmont, Missouri (See Map). The timely arrival of reinforcements allowed the Confederates to surround Union forces under Ulysses Grant, prompting him to remark that "we had cut our way in and could cut our way out just as well". The Kentucky again dodged shells to bring reinforcements to Brigadier General J. P. McCown as he sought to hold Island No. 10 in March, 1862.

Lodwick heard nothing more of his boat until June, 1862, when Memphis fell to Federal forces. He then proceeded to Memphis to claim his vessel but found on arrival that the Kentucky had been taken as a prize of war and was being used by the Unites States Army as an express mail boat, carrying freight, passengers, and produce from Memphis to Cairo, Illinois. TheKentucky had been captured by the Western Gunboat Flotilla, which was then part of the army but commanded by naval officers (the Fleet was transferred to the Navy Department on July 16, 1862). Between June 6, 1862, and February 4, 1863, the Kentucky served first the army, then the navy. Lodwick sought the return of his boat from Federal authorities and it eventually was restored to him by the U.S. Marshal on February 5, 1863, "in very bad condition". Years after the war, Preston Lodwick and his brother Kennedy fired a claim for charter fees of $200.00 a day for the 242 days that the Kentucky was in government service. After being bounced back and forth between the War Department and the Navy Department, the Lodwicks' claim was eventually denied on the basis of an Act of Congress dated February 21, 1887, which "prohibited the settlement of any claim for the appropriation of personal property where such claim originated during the war in a State declared in insurrection".

Six months after the Kentucky was restored to Preston Lodwick, his brother Kennedy and B. H. Campbell, she was chartered to the U.S. Quartermaster Corps for $80.00 per day. By 1864, the Kentucky was operating in the Red River and lower Mississippi River. The New Orleans Daily Picayune of May 5, 1864, noted her arrival with Captain Lodwick and 388 bales of cotton consigned to the U.S.Quartermaster. The Kentucky was still in service to the U.S.Quartermaster after the end of the war in 1865, transporting paroled Confederate prisoners out of Louisiana.

The Kentucky's Last Voyage

At 6:30 pm on the evening of June 9, 1865, the Kentucky left Shreveport bound for New Orleans with 800 passengers, baggage and provisions. For the most part, the passengers were paroled Confederate prisoners (some with their families), weary veterans of the Missouri, Arkansas and Louisiana regiments - the larger portion being Missourians that had defended Shreveport. Most of the prisoners had been paroled two days before and were eager to get home. Among the passengers were Captain Anthony Walton of Glasgow, Missouri, his wife, Mary Winn Walton, and their six children, ranging In age from four-month old Nannie to 18-year old Clemmie. Mary Walton and the children were crowded into the "Ladies' Cabin" on the aft portion of the boiler deck with the families of some of the other soldiers. Many of the paroled were sleeping where they could about the bow or in the forward cabin on the floor. The forward part of the Kentucky's main deck was also packed with 250 horses that the parolees had been allowed to keep after the surrender. To say the ship was over-crowded would be an understatement. Some two hours into her voyage, the boat struck a snag; one of the partially submerged logs that made the Red River notorious. By about 9:30 it was discovered that the boat had about two and a half feet of water n the hold.

No alarm was given to the passengers at first. Survivors of the sinking suggest that the ship's pilot wanted to make for shore but the Federal officer in charge of the transport ordered the Kentucky to keep moving down river. The vessel ran for about four miles after the leak was discovered, but by the time the captain finally turned for shore, the Kentucky had settled so much that he could not get near enough to the bank to put out his landing stage. A stern line was run to shore, but it snapped immediately. The boat swung out into mid-river, where the current is strong and the water deep and the bow was carried under, the boat careened over on side leaving only about 20 feet of the hurricane deck and the stern remained above water. As the boat heeled over, pandemonium broke out in the over-crowded decks below and passengers rushed for the hurricane deck. Adding to the confusion, the Texas deck caught fire as coal oil lamps spilled their contents. A largenumber of passengers were trapped in the forward cabin and drowned; estimates of losses ran as high as 288. The women on board, who occupied the ladies' cabin aft survived but several children were lost (The New Orleans Times, June 15, 1885). The loss of life was unusually heavy for a snagging accident.For some reason yet to be explained, the solders were permitted to remain asleep, in fancied security, while the boat had thus filled with water and was sinking; and thus nearly all of the solders were carried under with the boat. Some who were outside or could easily extract themselves, rose to the surface and swam out; some clambered up the sides and floor of the boat. Estimates of losses ran as high as 200. The heaviest loss occurred among those on the forecastle, composed of many Missourians.

A survivor of the wreck reported the horrifying events of the next few moments:

"As the boat careened a great rush took place to the hurricane deck. Many passengers were in their berths, and were saved almost wholly destitute of clothing. A large number were caught between decks and drowned. The ladies generally succeeded in gaining the hurricane deck and were saved, but some of the children were lost."Meanwhile, word of the disaster quickly spread to another steamer, the Colonel Chapin that had tied up for the night some 5 to 7 miles upstream. Captain Stephen Webber was aboard the Colonel Chapin when the news was received. He immediately ordered steam to be raised and set out to render assistance to the survivors. The vessel arrived on the site about 11:30 pm and found some 400 to 500 people crowded onto the elevated portion of the Kentucky. Webber succeeded in getting two lines from the shipwreck to shore and began ferrying the survivors ashore in two small boats. 18-year old Clemmie (Clementine) Walton, swam with her infant sister Nannie's gown clutched between her teeth, and had been pulled to safety on the shore. Mrs.Walton tells of how she gave out the "Masonic distress call" and soon she and her three other children were rescued from the wreck by the Colonel Chapin's boats. Her husband and son were among the missing.(Shreveport Journal July 10, 1974).

Reports of the missing and dead range from 20 to over 200. The official military report listed between 50 and 75 drowned. Bodies of the men trapped between the decks were pulled from the wreck for days after the sinking, while Mrs. Walton and her five surviving children sat on a trunk nearby. Her husband and son were never found and she and her live children eventually made their way to Missouri. (Shreveport Journal July 10, 1974). Most of the Missouri men were from the Pindell's 9th Sharpshooters division with others from the 2nd, 3rd and 4th Cavalry and 10th, 11th and 16th Infantry, Hooper’s Cavalry, Shank’s Cavalry and Elliott’s Cavalry Captain Webber was furious with the officers of the Kentucky, charging that their reckless decision to run the boat at night brought about a needless disaster. He later wrote to the New Orleans Times (June 16, 1865) that: “If I had the power, I would hang the captain and pilots to the first tree that I could find.”The Federal officer in command of the Kentucky who ordered the pilot to continue downstream made it to shore but hid in the woods till Federal troops arrived. A subsequent investigation by Union Major General Frances J. Herron, commander of the Northern Division of Louisiana, found the ship's officers innocent of any wrong doing, but resulted in an order prohibiting transports on the Red River from running at night.

In August of 1864, the 10th Missouri Infantry Regiment, U. S. A., returned to St. Louis to muster out at the expiration of its three-year term of service. The regiment formed in column and marched through the city, past the headquarters of General William Rosecrans, commander of the Department of the Missouri. They paused briefly at headquarters and gave three cheers before continuing the march. Then, a reception was held in their honor. The men spent the night at Schofield Barracks and then moved to Benton Barracks, where they made out their discharge papers. A month later, they were mustered out and sent home with pay.

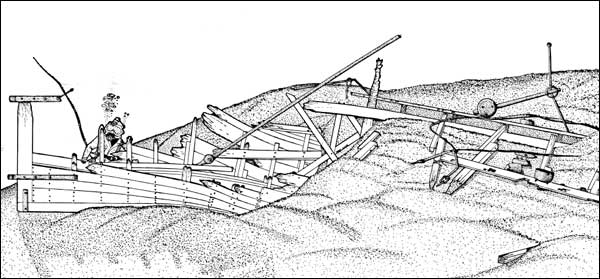

Homecoming for Missouri’s Confederate soldiers was a much different experience than it had been for Missouri’s Union veterans. On June 20, 1865, the veterans of the 9th Missouri Infantry Regiment, C. S. A., arrived at the St. Louis riverfront aboard the steamer Maria Denning. It was followed by the 8th, 10th, 11th and 16th Missouri Infantry regiments and the 3rd and 4th Cavalry Battalions. Before men were allowed to leave their steamers, they were required to take the oath of allegiance to the United States. Paroled officers and men of the late rebel armies were forbidden to wear the uniform, or any part thereof, or other insignia of said rebel service. Exceptions would be made, however, in the case of private soldiers who are destitute of means; they would be permitted to wear such clothing for a short period of time after stripping from the same all Confederate or state buttons and other insignia of the rebel service. No exceptions would be made for officers of any rank. Any violation of these terms would be considered an act of hostility to the United States Government, and the officers or soldiers would be punished accordingly. The survivors of the Kentucky sinking arrived on June 27.In the midst of the confusion and social upheaval that resulted from the end of the War Between the States, the Kentucky and it's gallant Confederate men aboard quickly passed from memory. No organized attempt to salvage the vessel appears to have ever been mounted although the hull continued to be visible in the Red River at low water as late as 1947. The remains of the Kentucky were investigated by the U.S.Army Corps of Engineers in 1995 before placement of stone revetment on the Red River. Archeological divers went down on the stern of the ship and entered it as far as they could. The majority of the ship was underground and the stern portion was encased in root mat, so little was recovered outside of horse bones, pots, personal items, the bilge pump, and the ship’s anchor.

After recovering what they could, the Corps moved the revetment away from the Kentucky leaving it buried under 25 feet of soil, safe from treasure hunters and looters. Most of the artifacts are now on display at the new J.Bennett Johnston Waterway Regional Visitor Center, a U.S.Army Corps of Engineers facility in downtown Shreveport.

A movement is currently underway by the descendants of the Missouri soldiers who drowned in the Kentucky to have a monument placed at the site.

Account of the Disaster from the Captain of the Colonel Chapin

“To Capt F.W. Perkins, A.Q.M. of transportation:Captain – I left Shreveport in obedience to orders from Major General Herron, thirty minutes past seven o’clock, June 9th. Finding it impracticable to travel after night, I landed the boat. The steamer Kentucky left previous to me about one hour. I presumed that all the boats would lay up together for the night. On proceeding down the river, I found the Kentucky against the bank, turning the point, and of course thought she was landing for the night. I therefore proceeded a short distance from her and laid the boat up. After being there a short time the Kentucky passed under a head of steam, at the rate of fifteen miles an hour, (to the best of my judgment) and had passed us somewhere between five and seven miles when she sank. I had the fire banked with the intention of remaining until daylight. After remaining about one hour and a half hours I was notified from shore that the Kentucky had sunk, and that the assistance of the boat was required to prevent further loss of life (a great many having already been drowned) and destruction of property. I immediately raised steam and got under way, Arriving at the wreck about half-past eleven p.m. I found everything in confusion, and endeavored with all available means on board to secure men and women. I immediately lowered a boat and went in person to the boat; found no boats yet at work. I at once stretched a trail line to the shore, to run boats by, the current being too strong to use sweeps or oars. My first mate directly afterward stretched another from the starboard after cabin guard, when we set two boats to work, having procured one from the neighboring plantations. We eventually got everyone off who wished to come, some remaining on onboard – for what purpose I know not. The whole affair is very disastrous, involving a great loss of life, and in the opinion of all high minded and honorable men, as well as some who were on board with these officers of the boat, and also in my opinion too, the disaster could have been avoided, and that it only resulted from inattention and ignorance, as an investigation of the same will prove. During the rescue of the people on onboard, and while running my small boat in person, I made use of the following language: “if I had the power, I would hang the captain and pilots to the first tree that I could find,” an assertion that I am prepared to maintain. Having ascertained indirectly that the officers of this boat intend reporting me for the use of the above language is the cause of my making this statement, as I know that they are wholly incompetent to command or have charge of anything regarding transportation, where human life is concerned.”

Stephen J. Webber

Captain Commanding Transport

June 10, 1865

An entry in the diary of Marcus M. Rhoades of the 9th Missouri Infantry describes the arrival of the 2nd Mo. Brigade (10th, 11th, 12th, 16th Mo Infantry, Pindall's Mo. Sharpshooter Battalion, Leseuer's Mo. Battery) at Baton Rouge, four days after the sinking of the Kentucky:

"Baton Rouge, June 13, 1865.

C.S. troops of the 2nd Mo. Brig. arrived today from Shreveport. They report that the steamer Kentucky sunk twelve miles this side of Shreveport drowning from 100 to 150 persons, and among the number was Mr. Dickey Robertson. The 8th and 11th Mo. Infty. went aboard the Steamer Stickney for St. Louis. About 2 p.m. the steamer Maria Denning hove in sight coming from New Orleans, and moving like a snail. Very large boat used for transporting stock. Can take C.S. troops beyond a doubt. The 9th Regt., Searcy's Battalion Mo. Infantry, Ruffner's Battery and a few cavalry all on parole-amounting to about 1700, went aboard. Including all, there were quite 2,000 souls on board."

Statement of James T. Wallace of Co. D, Pindall’s 9th Battalion of Missouri Sharpshooters regarding the sinking of the "Kentucky".

"…We are furnished transportation on old steamers for Baton Rouge. We are placed on board the "Kentucky," a miserable old hull and shipped for home. When about 25 miles down the Red River, at 10 o’clock at night, the alarm was given that the boat was sinking. The greatest consternation prevailed among those on board. Many being suddenly aroused from sleep, rushed forth in their night clothes and leaped wildly into the angry waves overboard. The confusion seemed to bewilder many who lost all presence of mind and rushed about frantically and aimlessly. At one time I thought I would be drowned in the cabin of the boat before I could escape. The boat suddenly careened and settled almost upon her side before she touched bottom. The cabin was rapidly filling and all chance of escape seemed gone, but she settled back and we reached the hatch to the hurricane deck. I felt a measure of relief when I had the open river before me. I deliberately took a door from its hinges and threw it upon the water near the stern of the boat and then committed myself to the water. Although at the greatest distance from the shore, I had the advantage of being alone, and I reached the shore without great difficulty with all my clothes on. Many a poor fellow who leaped off in the great crowd near the bow was dragged down by others in their dying struggles. Capt. Kendrick [Capt/Major G.S. Kendrick- Pindall's 9th Battalion] only escaped the death grasp of a heavy colored woman when he, by a desperate effort, tore off one whole leg of his pants. The scene was painful in the extreme. It seemed especially hard that this sad thing should happen just when we were on our way home. Almost 65 soldiers were supposed to be lost. 3 out of our company perished in the waves. Joseph Wilson, Washington Burkhart, and John Burns."

Account of John D. Waller, Leseuer’s Missouri Battery, regarding the sinking of the "Kentucky."

"Friday June the 9, 1865. …About sunset the 10th, 16th, and the battery (Leseuer’s) were put on board the "[E. H.] Fairchild," Pindall’s Bat. and stragglers on the Kentucky, which left this evening. We will leave in the morning…""Sat. June the 10. On board the steamer "Fairchild" bound for Baton Rouge. Report that the "Kentucky" sunk last night 20 miles below here. We left port at sunrise about 8 A.M. We came in sight of the wreck of the "Kentucky." The report was too true. She had sunk about 9 P.M. and was an entire loss. About 100 persons perished, mostly Negroes and some children. One Mo. lady, God bless her, swam to shore with a child in her teeth. 15 of the brave sharpshooters were drowned. This was truly distressing. Friends that had shared the hardships of war for 4 years that had fought shoulder to shoulder on so many bloody field separated just on their way home where all is that is near and dear to them now. It made my heart bleed to see them without clothes, shoes, or hats. The boys divide all they had with them. Gen. Herron ordered them back to ships for rations and clothes. He is very kind."

Account of William N. Hoskin, Leseuer’s Missouri Battery, regarding the sinking of the "Kentucky"

"June 10 Sat. Being loaded last night on the "E. H. Fairchild", we leave this morning at sunrise, about 1000 on board. Bad luck to the "Kentucky" last night, snagged and sunk with a number of lives lost—a number of children, Negroes, horses, most all baggage—supposed to be done intentionally. The boat is all shattered to pieces and broken down in front. After stopping an hour or so we pass the wrecked boat. Those who had been shipwrecked being supplied the best that could be by the men on the other boats. They took another boat, went back to the port (Shreveport) to get rations and paroles, many having lost the former ones…"June 15 Th. …Seven dead men seen in the water today, one taken out of the wheel house of our boat, supposed to be one of the men drowned on the wrecked "Kentucky," known by some of his friends…"